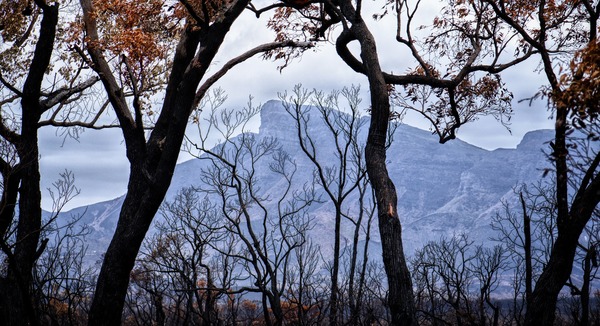

A peer-reviewed scientific review has found native forest logging makes forest more flammable and leads to elevated fire severity for several decades, whilst “mechanical thinning” of forest can actually increase fire risk in some cases.

These were two of the key findings of an expert review of 51 peer-reviewed scientific papers by The Bushfire Recovery Project – a joint project between Griffith University and the Australian National University to inform the public about what the peer-reviewed science says about bushfires. This was done through a series of expert reviews of the scientific evidence, providing an overall picture for the public.

The expert review (meta study) assessed the data and findings in 51 different peer reviewed scientific studies, including those which measured and compared how hot or severe fire burned in different areas during the same fires.

Other key points included:

– The key contributor to increased bushfires and damage from them is climate change

– The data shows native forest logging increases the severity at which forests burn, beginning roughly ten years after logging and continuing at very elevated levels for roughly another 30+ years (data from Price and Bradstock 2012, Taylor et al 2014, and Attiwill 2014, as well as US studies)

– The data shows the likelihood of “crown burn” (when the forest canopy is burned) is around 10% in old growth forest and around 70 per cent in forest logged 15 years ago. The likelihood drops steeply but continues to be elevated for decades

– This is likely because thousands of young trees regrow, creating increased fuel load after the forest canopy has been removed, and many of those young trees then die, becoming dry and highly flammable

– Lack of canopy results in increased sun and wind drying the young plants and soil, and increasing wind speed on extreme fire days

Multiple studies have found “mechanical thinning” does not decrease fire risk; one study on Alpine Ash forest in Victoria showed “mechanical thinning” decreased surface fuel but increased coarse woody debris by 50 per cent and increased the density of saplings tenfold (Volkova et al., 2017)

Professor Brendan Mackey, Director of the Griffith Climate Action Beacon, said while the key contributor to increased severity of bushfires was climate change, several peer-reviewed scientific studies had also shown previously logged forest burned hotter than unlogged and old growth forest during fires.

“The data in Price and Bradstock 2012, Taylor et al 2014, and Attiwill 2014 all show that forest regrowing after logging burned more severely than unlogged forest during Black Saturday 2009,” Prof Mackey said.

Dr Chris Taylor said the general trend found in the evidence across scientific studies was that forest began to be more flammable eight years after logging.

“The relationship between the forest having been logged and how severely it burns during a fire is quite clear,” Dr Taylor said.

“The data across multiple peer-reviewed studies shows the likelihood of “crown burn” (when the forest canopy is burned) is around 10 per cent in old growth forest and around 70 per cent in forest logged 15 years ago. The likelihood then drops, but continues to be elevated well above that of old growth forest for decades.”

ANU Professor David Lindenmayer AO, who has been keynote speaker at logging industry conferences, said the link between fire severity and logging had been found in global studies including in the US and Patagonia.

“Locally, a fire severity map analysed by Cruz et al suggested the Kilmore fire burned less severely when it entered old growth forest at Wallaby Creek on ‘Black Saturday’ in 2009,” Prof Lindenmayer said.

“Logging typically takes only the trunk of the tree, with the branches, top of the tree and the bark left dead in the forest. Some logging operations (mostly in Victoria) burn the forest after logging, but Keith et al 2014 found up to 50 per cent of the woody fire fuel can remain even after that.”

Dr Patrick Norman with the Griffith Climate Change Response Program said the increased flammability shown in the data was likely because removing the canopy increases sun and wind, which dries the forest out, and rapidly growing, dense young trees create increased fire fuel, partly due to their high death rates. Higher wind speed is also a key factor in extreme fire conditions.

For more information, visit bushfirefacts.org